Soerabaia

Indonesia was on my short list of countries to visit, and in late 2024, an opportunity arose. I planned to visit Sorong in what was once Dutch New Guinea, a place where my father lived in the early 1960s, and to explore the ancestral village of a close friend, Nenik, in East Java. I flew via Singapore to Surabaya, and to my surprise, her entire family was at the airport to greet me. My first lesson: in Indonesia, you don’t travel alone.

While Tanjung Priok, the port of Jakarta, is more prominent, my father’s steam- and motor ships from the Rotterdamse Lloyd also docked in Tanjung Perak, the port of Surabaya. Most Dutch sugar factories were located just south of Surabaya, and I can imagine that this port city, spelled Soerabaia on an old Dutch postcard, was used for the majority of sugar exports. By the 1950s, Surabaya had become part of Indonesia, yet Dutch ships continued to sail their routes.

Nasi Bebek Hitam Spesial

I spent the first afternoon in my hotel room, trying to sleep off some jet lag. In the evening, I learned a new word: "hitam", which means black. This was in conjunction with my first dish, Bebek Hitam (black duck), featuring fried duck (bebek goreng) in a spicy black spice blend (bumbu hitam pedas), accompanied by lalapan (raw vegetables) and serundeng. The duck was so tender that I even ate the bones. It was a fantastic start to my culinary journey and a remedy for jet lag—at least that’s what I told myself. The price: 33,000 Indonesian rupiah (2 Euros). I drink black coffee so I quickly realised that I had to order Kopi Hitam.

The usual means of transport in many Asian cities: the scooter with a combustion engine.

My first impression the next day was of the breakfast courtyard at the five star Bumi City Resort Hotel. It felt warm, reminiscent of the tropical butterfly greenhouse I remember from Dutch zoos. As a child, the hot and humid greenhouse was my favorite part of the zoo. Now, I was having breakfast in a tropical greenhouse, and I was enjoying every moment of it.

One of my favourite dishes: pecel sayur. Because of the spicy pecel peanut sauce this is not gado-gado, a similar dish but made with a different bumbu kacang or peanut sauce.

Even though it was the rainy season, the weather hardly bothered me; the rain showers were quite brief. In the morning, I wanted to visit the harbor to experience its atmosphere. During my father’s maiden voyage with the steamship Overijsel, he didn’t reach Surabaya, but he did with later ships, the s.s. Tomini and the motor ship Kota Baroe. In 1955, my father signed off with the Rotterdams Lloyd.

Motor ship Kota Baroe leaving Rotterdam. Date unknown.

Liberty ship s.s. Tomini, built in 1943.

It is interesting to note that not all shipping lanes were between Asia and Europe. The Java-China Japan Line (JCJL), founded in 1891, maintained a network of shipping routes connecting Java, China, and Japan. Exports from Nederlands-Indië were finding markets in China and Japan.

View from Surabaya North Quay

The North Quay is open to the public. With a small entrance fee, you can access the second floor of the cruise terminal, which features a food court and views of the harbor. While there wasn't much to see, I specifically wanted to visit the harbour so we could slowly backtrack to the hotel and see the entire city.

The 10 November Museum, located beneath the Heroes Monument, was closed on Monday, so we decided to visit Chinatown and the Roode Brug instead. Surabaya's Chinatown is primarily a hub for Chinese traders, with the main activity consisting of trucks unloading boxes into small warehouses. This Chinatown does not cater to tourists.

The Chinese restaurants in Surabaya China Town are spartan.

It might not be a surprise that the “Roode Brug” gets its name from the distinctive red color of the bridge. During the Dutch colonial era the bridge served as an important transportation link across the Kalimas River.

While I am interested in architecture, there was not enough time to really delve into Dutch colonial architecture and what remains of it.

The Cigar Building (Gedung Tembakau) on Jalan Rajawali in Surabaya.

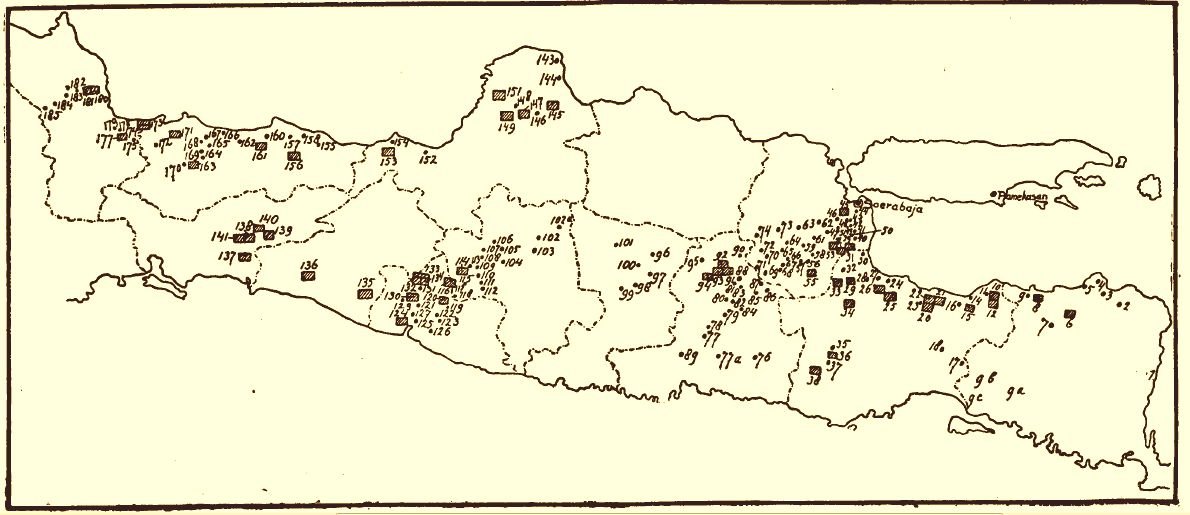

The distribution of sugar factories in Dutch colonial Nederlands-Indië highlights the importance of Surabaya as a port city and its influence on the current road and railway network in East Java.

Complete list of sugar factories in Java on 11-02-1932.

Metropolitan Police Museum

While visiting the Museum Hidup Polrestabes (Metropolitan Police) in Surabaya, I realized that Indonesians love to take photographs. It seems impossible to have a conversation without ending up posing for a picture together. I even found myself in a photo with the man who exchanged my euros for Indonesian currency—it’s a bit wild. The museum is housed in the old Hoofdkantoor van de Politie from the Dutch colonial period. I posed in front of weapons used in the aftermath of World War II. I immediately recognised the Bren light machine gun.

Detail of a painting in Museum Hidup Polrestabes.

“Nieuwe Zakelijkheid” in Indonesia

Gebouw van de handelmaatschappij Borsumij aan de Sociëteitsstraat te Soerabaja, ca 1936

If you love architecture, Surabaya has some hidden gems. Dutch architect Cosman Citroen (1881-1935) designed the office for the Borneo Sumatra Maatschappij (Borsumij), which was built in 1934 and completed in 1935 in a modern style influenced by the Nieuwe Zakelijkheid.

Citroen was well known for his Surabaya City Hall (1925). The city hall was build in the Nieuwe Indische Bouwstijl (New Indies Style), early modern (western) architecture (e.g. Rationalism and Art Deco), applied to local architectural elements suitable for the tropics.

Citroen passed away shortly after the Borsumij office building was finished, unaware that just over a decade later, a devastating world war would have occurred and that the Dutch would have relinquished control of Nederlands-Indië.

Surabaya’s role in the independence movement

This is not a real car but a replica of the 1940 LaSalle SB 723 sedan used by Brigadier A.W.S. Mallaby of the British Indian Army. In 1945, he attempted to negotiate a ceasefire between British forces and Indonesian nationalists in the post-war power vacuum. The British forces were tasked with re-establishing Dutch control; however, Mallaby's convoy was attacked in Surabaya near the Roode Brug. A photo taken in 1945 served as a blueprint for the current monument. His death led to the Battle of Surabaya in November 1945, culminating in a large-scale operation on November 10. This day is now commemorated as Hari Pahlawan (Heroes’ Day) in Indonesia.

Pecel lele

This fried catfish dish comes from Lamongan Regency, located near Surabaya. It was one of the meals I had been looking forward to before my arrival, so when I spotted fried catfish in a small warung, I couldn't resist. The catfish used is a freshwater variety. Pecel lele is typically served with sambal, steamed or fried tofu, and in my case, a small piece of cooked banana. The cost of this dish is usually very affordable; I paid less than one euro for the fish, vegetables, and white rice.

Indonesian food courts are usually bustling with numerous small restaurants operated by independent entrepreneurs.

Cocote Tonggo, Ceker Pedas! "Your Tongue, Spicy Chicken Feet!"

By chance, we stumbled upon this little eatery. The number of scooters parked outside quickly led me to believe this was the best spot for cheap and delicious food. The customers were predominantly young. The menu is straightforward: they wok either shrimp (udang), mussels (kerang hijau), cockles (kerang dara), chicken intestines (usus), chicken feet (ceker), or chicken wings (sayap) in the same spicy sauce. You can choose from five levels of spiciness: original, lamis (5 chilis), lower (10 chilis), lincah (15 chilis), or rusak (20 chilis). I opted for a safe choice of 15 chilis. "Rusak" means "damaged," and that sounded a little intimidating. In hindsight, I could have handled the 20 chilis. Yes, I had the mussels with chicken intestines, and it was one of the culinary highlights of my entire journey. The sauce was complex and flavorful. As we walked out, all the chefs clapped and cheered for us.

Most people eat with their hands in Indonesia.

The phrase "Luweh huenak teko cocote tonggomu rek?" translates to "Is it more delicious than your tongue, right?" in English. The place has a strong presence on Instagram and uses playful local crude Bahasa Jawa slang in their advertising. In principle, every Indonesian is bilingual. The official language is Bahasa Indonesia and in addition, each island has its own language.

On the last night before our flight to Sorong, we decided to indulge a little at the bar of the Bumi City Resort and we ordered mocktails. I chose the Mint Rock, made with non-alcoholic rum. It arrived with a small sign that read: "I sat in silence, finding the dark side of myself in every sip of my drink." Don’t we all have a dark side?

“Aku duduk dalam diam. Menemukan sisi gelap diri, dan di tiap sesap minumanku ini. ”